Apple Tax, Populism, and the Persistent Fallacy that Accountancy is Economics

Tax and tech are entering their accountability era. The Irish State, which has both enabled and benefited from the previous Wild West era, faces the prospect of not just an economic but also a political crisis if it doesn’t adjust.

The Apple tax case has crystallised for me the idea that the National Business Model really is coming to the end of its useful life; and that the consequences of that are deeply politically destabilising, as well as economically frightening.

Here is my take:

Making hay while the pennies-from-heaven shine

In the Apple tax case, which was finally put to rest this week, the State found itself in the humiliating position of spending a decade and €10m in legal fees fighting against collecting taxes that Europe says were owed to it. And then losing.

This damaged our reputation internationally, but it has also undermined the credibility of the State at home. Both the opposition and extremists are making hay, mocking the doublespeak of state institutions fighting against revenue in a cost of living, health system and housing polycrisis.

Successive ministers have had to stand up and say, with a straight face, that “Ireland does not do deals with taxpayers”, when the evidence available to the public showed in black and white that companies are paying below 1% in tax.

We signed off on creative accountancy that allocated billions of Euro of global profits in Ireland. This is despite, in Apple’s case, the country not having a store here, and the products in our pockets proudly declaring, in writing on the back, “Designed by Apple in California, Assembled in China”.

Creative accountancy as a business model

As we all know, there has been broad political consensus since at least the late 1980s on the national business model underpinning these actions, as well as tacit public acceptance; create good tax paying jobs through encouraging foreign direct investment; encourage that investment by being an attractive and stable location for long term investment.

Central to that competitiveness is being more attractive and stable on corporate tax.

This was an economic system built by accountants and lawyers; the Finance Ministers of the era were literally either accountants (Bertie Ahern, Charlie McCreavy), lawyers (Brian Cowen, Brian Lenihan), or both (Charles Haughey).

But accountancy is not economics.

Enabling creative accountancy might provide stability for firms; but building an economy around enabling creative accountancy provides the opposite of stability.

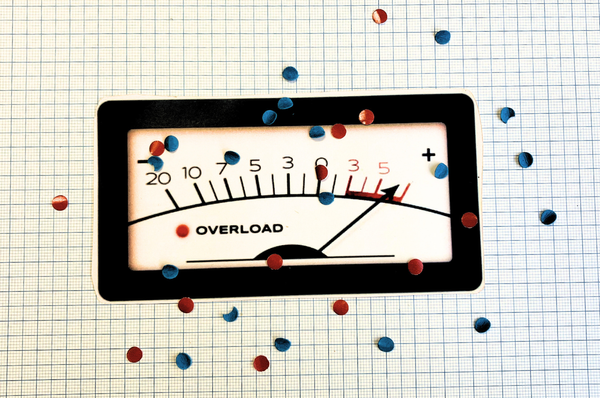

We have gotten away with it thus far, but it has created deep instability on our national balance sheet.

The world is catching up on creative tax practices. We are in a brief window where, ironically, the crackdown is benefitting us, but it will not last. The Fiscal Council tells us three multinational firms paid 43% of the tax in 2022, and that without the current windfall taxes, Ireland we would all be paying an extra €3,600 tax.

In fairness to the Government, windfall tax is something that is openly acknowledged, and much of the additional revenue is funnelled into long term funds. There is a push to grow the real domestic economy and resulting tax revenues, with smart investments made supporting export oriented domestic business, especially in areas where we excel like the food and beverage sector.

A new vulnerability to leverage

Yet we find ourselves beholden to the whims of global capital, working to identify compelling new competitive advantages. Industry knows this too, and is leveraging the state's new vulnerability.

They are using that power to lobby for things that are deeply unpopular with voters. Ibec declared last week that “tax is not a competitiveness calling card any more”, that can “paper over” infrastructure gaps. They specifically call out “clean, competitive energy, plentiful water supply”, essential infrastructure for data centres.

Amazon is one of many companies lobbying for more data centre, who back in June “clearly feels that a €17 billion investment and 6,500 jobs entitles it to bluntly tell the taoiseach of the day that Ireland needs to up its game or risk losing out on future US investment.”

An unenviable choice

This is where we see alternatives to the low tax offering threatening new levels of political instability, on top of fiscal uncertainty. Data centres are the key infrastructure of the coming AI era, but data centres are not job creators, and it remains to be seen what the impact of AI will be more broadly on labour. They are also not popular; polling shows that nearly 3 in 5 Irish people support an indefinite pause in their creation.

It is also not popular to try to compete on low regulatory enforcement, another card Ireland is accused of playing, especially when the EU’s “country of origin” rules give the state a monopoly on implementation of many block wide rules. As the EU cracks down on platform accountability, any attempts to provide under-enforcement will not be popular. Two thirds of the Irish residents believe social media platforms are not doing enough to prevent harmful content being shown to users.

The old national business model served us well, until it didn’t any more. We shouldn’t forget that the other component of our 80s and 90s economic model was the policies that led to the housing bubble and the economic collapse of 2008. As well as hardship, that crisis led to a globally resurgent far right and to populism. We clung to those policies for too long, and paid a price.

Conceding to threats and ultimatums from industry now, may not only fail to deliver economically, but may further undermine the credibility of the state, and embolden those offering easy solutions of which, if we are very honest with ourselves, there are very few.